Managing complexity in large scale processes

Thinking big with Solution Focus

May 16, 2021

Unusually we have not written an introduction or commissioned a review for the following article.

The introduction to the article introduces it perfectly, and the editorial team thought we would experiment with a new idea: to let you the contributors discuss and review the ideas in the article on the [LinkedIn group].( https://www.linkedin.com/groups/13507275/).

We would like to give grateful thanks to Jonas Wells from Sweden, for kindly contributing and reviewing in the article, the description of his work within the Swedish context. The article has been changed and extended from the original version.

John, Carey and Annie – InterAction Editorial Team

Introduction

“Thinking big” is about dealing with issues such as how to resolve or navigate climate change, to look for life on other planets or design future cities that strengthen peaceful co-existence. It is about how to translate the atomic model into inventions like CDs and computers, finding new ways to negotiate agreements at the UN. It is also about learning patterns in kindergartens, creating alternatives to unemployment, having police officers change communication with citizens, as well as about dominant perceptions on refugees.

These are big issues and indeed diverse. Nevertheless, the common aspect is without any doubt that “thinking big” is closely related to something large-scale. If we look to the dictionaries, “large-scale processes” are predominantly limited to being defined as: “Involving large numbers or a large area; extensive”.

Based upon this perception of “large scale”, in the solution focused context it could refer to a coaching session for a couple that have a huge influence over a big area, or it could relate to changing processes in an organisation with a large number of people. Any change in these extensive organisations could potentially involve hundreds of thousand, or even millions of people, if we include their users or consumers. However, I am not referring to these processes.

In this article, my point of departure is that “big” and “large scale” not only have to do with involving many people, but also about how people are involved and what for.

Large-scale perspectives, in the sense I am pointing at, include changes that always have a direct or indirect impact on a large number of people, different groups, sectors and areas. Their impact is usually diverse and on several levels at the same time. These processes are highly complex and can rapidly change direction, form and impact.

With this focus on managing complex change processes, I am inviting you to seriously consider the use of SF in large-scale processes, be it as an essential perspective in public policies, implementation of reforms, invention of technologies or any initiative that may have a multifactorial impact in different ways and levels.

However, since putting this specific title on the topic, I have reflected on its accuracy. I have repeatedly found myself trying to identify if this is actually about thinking big with SF or about SF in big thinking in general. This may sound rhetorical, though perhaps it is not. Perhaps this is indeed a very important difference.

Nonetheless, for now, I will leave it here and invite you to let the following moments be a tiny peephole through which a world with SF applied in large-scale processes can be glimpsed.

Imagine that SF was integrated systematically in large-scale processes.

What would be different? How would that show?

Experiences large-scale

My way to SF Large-Scale started on the streets in Mexico City with gangs and informally organized crime. As a social anthropologist, I was supposed to do field work, and I had chosen a topic related to the social impact (and what might be a repressive character) of the values promoted by the UN on human rights. Nevertheless, different circumstances made me change the subject, integrate with adult street gangs and write about how to deal with the multiple contradictions you are confronted with, living constantly on the edge. The person next to me could at one moment kill or rape, and the next, save a child or take on responsibilities to help unknown elders. That was indeed simultaneity between strong contrasts.

In these extreme conditions, coexistence demanded a more diverse perspective on judging. Working with those gangs, I understood that recognition is much more than being positive towards someone. It is about taking the value of others seriously, independently of whom they are or what they do. I searched on how to question people and events without letting recognition out of sight, and without moral judging.

In this search, I stumbled over some books on SF that offered exactly that. Since then, I have integrated SF in everything I do large-scale.

I have worked on public security issues. This has involved working with police organisations on reducing conflicts between police and citizens in states with wars among drug cartels and where police killings on civilians were on the rise. Without ever mentioning the killings, we explored how a “normal” day would look like for the police in their description of the future. This neutral question offered each of them room for being seen as someone other than police officers in need of being fixed before potentially becoming assassins.

From this platform, we could work on how the relation with citizens might be in those imaginary situations, and how society would notice the change. For many police officers, just imagining the future changed their perspective on their present. They usually thought they were not going to survive one more week, which made them indifferent to the consequences of their actions. Why care about citizens if they were about to die anyway? Nevertheless, suddenly it mattered what they did today. Tomorrow was waiting.

When the world of consultancy on public security in Mexico was competing to come up with the best methods for measuring how deplorable the police was, SF offered a completely different perspective, that for a moment opened up room for new encounters between the police and citizens.

Social conflicts have been at the core of many projects of mine. This has also included participation in the implementation of the Energy Reform that Mexico recently approved, and that implies breaking up the State monopoly on exploitation of gas and petroleum, allowing private oil companies to exploit these natural resources. This turns many states of Mexico into symbolic fields of land mines, where social conflicts are just ticking. Some indigenous people are fighting against the destruction of their land, while other villages seek collaboration and so-called development. On the other hand, we also find large profits are made by those who saw the reform coming, including the mafia, and a government having to deal with multiple interests and risks without losing the enormous investments the energy sector offers.

An initiative of the federal government to reduce social conflict in this field was to establish a special negotiation office with responsibility for preventing and managing complicated scenarios between private companies and landowners. In that setting, as an adviser for the federal negotiations office, I used SF relational questions to map the interests, risks and possible scenarios between all agents directly or indirectly involved and affected. What difference did that make? The insistence on focusing on relations, diversity in perspectives and noticeable differences, as well as the constructive way of simultaneously searching for solutions in the past, present and in the future made the difference. This non-lineal way of designing and planning a public programme, permitted the integration and management of this complex reality to a greater extent. Among other results, this was transformed into the first programme for governmental mediation of energy conflicts in Mexican history.

In 2013, Mexico City’s High Court of Justice approved a reform of the Law of Alternative Justice, which provided all court notifiers and executioners the faculty to mediate between the parties in legal conflicts. This was an important contribution to an already highly advanced legal system of alternative justice in Mexico City’s High Court of Justice. For me, that was also the beginning of more than four years as coordinator of and permanent adviser on designing a system for the implementation of the reform as well as making it operational. SF was the backbone in every step of this work, from creating a system of collaboration and evaluation, to designing official procedures, information campaigns for the citizens, the development of new software for collecting data as well as aspects of the political strategies for positioning the High Court on this issue.

Along with the initial training phase of the first 200 court notifiers and executors in conventional mediation principles and techniques, they were also trained in the basics of SF. In this interaction with the Court personnel, it became apparent that the success of the implementation of the alternative justice reform mostly depended on a change in the way the notifiers perceived themselves and were perceived. In other words, unexpectedly it was not an issue on teaching techniques and making programmes but identifying the questions that could create the necessary platform for action. Many of them were formulated in close collaboration with the court personnel themselves. What changes did they need to notice in interaction with judges and citizens so as to perceive themselves as mediators? How would they know that change was worth it? What could help the Judiciary Council to notice that the reform had succeeded?

Well before the reform’s implementation was finalised, judges and notifiers started talking about constructive changes taking place without them being part of the planned results: Fewer complaints from citizens; higher efficiency in notification; operational initiatives never seen before and even more surprisingly, a reduction in corruption.

However, in the precise moment when thousands of public servants were about to get involved to implement a programme offering court mediation for Mexico City’s 25 million citizens, a new President of the High Court was elected. Priorities were redirected and the programme was put on hold. Afterwards it has become clear that though a programme can be stopped, the changes achieved will prevail.

Throughout the years, I have used SF for furnishing a different perspective on public policies, participating in national negotiation strategies, designing multiannual institutional agendas, contributing to managing social conflicts or training for cultural change…

SF has simultaneously been my navigation compass and the means of transportation.

Recently, it has become clear to me that we are still very few in the world using SF in large-scale process. Thus, I was intrigued when I was introduced to the Swedish Coordination Manager, Jonas Wells, who is working with financial coordination of joint efforts between various public sector organisations in the field of vocational rehabilitation in Sweden.

While I learned about Jonas’ very interesting job, I couldn’t help paying special attention to the description of his work that pointed at a culture of dialogue very far from the communication known at work in Mexico. It is often emphasised that in Sweden, and more generally in Scandinavia, the dialogue seems an aim or a priority in itself. The creation of the Coordination Agency in Sweden that Jonas is managing, as well as the will to keep trying out the application of SF in the public sector, is precisely a confirmation of that priority. It does not mean that constructive dialogue is automatically integrated, but that the idea of investing time, resources and hard work into it, is part of the daily work. This is indeed different from most working environments in Mexico, where the conditions for creating dialogue frequently do not have any place at all, and it is rarely considered a necessary or positive step in the process.

The space for dialogue in Sweden seems related to a more egalitarian working environment that permits people to communicate even though they are positioned at different levels in the hierarchy. This is much more difficult in Mexico, considered one of the most “vertical societies” in the world, which, among other things, can be noticed in the radical distance between levels in the hierarchy. In Mexico, leaders are not to be questioned openly and it can have strong consequences to show any kind of “weakness” at work, including, for example, showing doubt, asking for help or integrating people in planning processes who are not part of an exclusive group of strong personal relations close to the leader. In Sweden, the focus on dialogue and the idea of striving for ever more equality at work allows a very different frame for working Solution Focused. This stood out when Jonas told me about, for example, Mayors having sessions together to engage in dialogues about how to improve planning. As part of creating the correct environment where confidence, dialogue and creativity could lead the way, they even introduced the session with music and a playful atmosphere. In Mexico, a framework like that would not be an option as it might make the participants feel at risk of being exposed and any use of informal or playful elements would most likely be seen as a strong disrespect for the authority and have negative consequences for everyone involved.

What Jonas described about the context of his work represented deep contrasts to my working environment, where I am dealing with a strong and solemn hierarchy, radical instability, ever present security issues related to corruption and threats of different kinds and, particularly, pronounced power games.

How could these two environments and ways of using SF large-scale possibly have any similarity at all? As it showed, it had.

Identifying characteristics

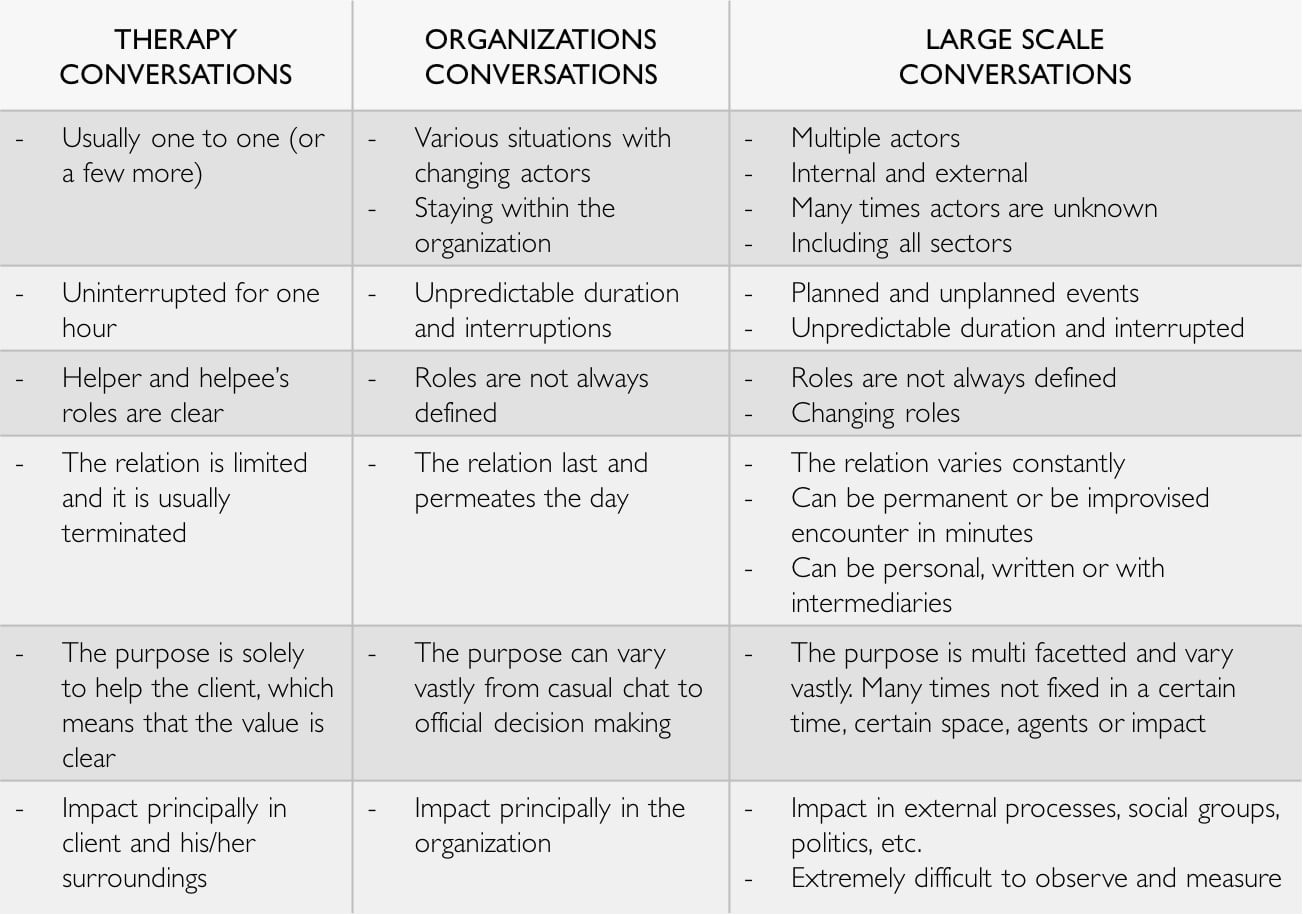

For almost a year, Jonas Wells and I analysed characteristics in our working methods, compared them frequently and interviewed each other long distance to explore details. At first, while looking for common characteristics in our large-scale role we inevitably became aware of the differences between this way of using SF in comparison to more common settings for SF, as for example in therapy and organisations.

To make this clearer, we added large-scale conversations to the comparison table of the most common types of SF conversations, originally developed by the Japanese SF consultant, Yasuteru Aoki:

What stands out here is the simultaneity between being inside and outside of the process. Where the SF Therapist usually has a very clear timeframe for his / her participation, and the Organizational Consultant comes and goes at certain moments agreed upon beforehand, it is common for the SF large-scale consultant to be part of the everyday work, however, in different roles as, for example, a leader, operative coordinator or adviser.

It is an interesting condition as it demands being especially aware of when to use SF and when not to. As conversations are not necessarily planned, the best moment for using an SF perspective may rightly be anywhere; e.g. in the elevator when finally having a private moment with the Minister. That can make it necessary to constantly prepare and update some kind of battery of carefully formulated questions to apply whenever the opportunity shows. There is definitely much to explore in this state of being inside and outside at the same time, which may tell us more about what we do when we decide to apply one tool instead of another, in one particular moment instead of another.

The characteristics described, also call for a second glance at the fact that most SF in large-scale processes is done “undercover”, in the way that the role is not openly Solution Focused. We are doing something that works, but there is rarely any interest in knowing what it is. On the contrary, in my experience it has even been an obstacle to try to bring descriptions about SF into work. I have found that doing it “undercover” is the easiest way, and oftentimes the only way, to succeed with using SF for thinking big in large-scale environments. However, I wonder if the time is now ripe to try to publicly create awareness about SF and the benefits of using it. I will share this curiosity with you, asking: “What would be different if SF large-scale was known worldwide for being an efficient contribution to meet the enormous global challenges awaiting us?

Benefits

In recent years, it has become clear to many agents involved with large-scale processes that the tools commonly used are not flexible enough when applied to a world with more complex challenges and more rapid changes than ever. This has opened up systemic approaches as well as experiments with complexity, as for example through social media, where even political campaigns take place. While this has been increasingly important in large-scale projects, national and international planning, it seems that it is not enough for managing complexity successfully.

And here is where SF can offer something different:

It is more efficient in non-linear planning, among other reasons, because it brings to the table many perspectives and the small and constant adjustments needed when implementing large-scale changes. Moreover, it also makes it easier to integrate diverse perspectives simultaneously without perceiving them as confrontational or having incompatible interests or juxtaposed positions. It makes complexity more visible, but through tangible, noticeable outcomes.

SF does not stem from the idea of how to avoid or prevent uncertainty and unexpected changes. On the contrary! That is in the essence of SF. Another important difference is that the use of SF tools assures an essential recognition of the people involved or affected directly or indirectly. This is manifested through the questions exploring impacts in another way, as we strive to visualise even the smallest of changes, what difference these would make as well as the relations between different agents, settings, sectors and environments. And these questions take their point of departure in SF assumptions that easily escape description. It looks as if this process depends on some kind of confidence or faith. Faith in the process, its tools and the room for change.

Using SF to design, implement and coordinate large scale processes certainly raises the possibility of achieving constructive change faster and in a more sustainable way.

Altogether, in line with Steve de Shazer’s idea, this is definitely “a difference that makes a difference” when implementing large-scale processes or changes. SF offers an enormous potential large scale, just waiting to be unleashed.

We have seen what happens when similar tools have been used around the world;

A case in point was the successful negotiations of the Paris Agreement on Climate Change, where they applied new dynamics related to an African method that assures the integration of different perspectives and details. There are many other examples, from new ways of using future visualisation with questions similar to the SF ones, to engage civil society in peace building and national planning endeavours.

In my perspective, there is no reason why SF is not a permanent and visible part of these kind of processes.

This, of course, does not mean that thinking and acting large-scale with SF, is devoid of risks. This is definitely not the case.

Critical reflections

The moment SF is applied in large-scale issues, it also deals with settings of intensified power struggles, conflicts and opposing strategies. Therefore, it also follows that:

• It is often difficult to determine or verify how SF is used, for whom it is meant and what strategies are part of it.

• This potential lack of transparency may potentially imply that the project and its impact are not even coherent with what was the point of departure.

• Solution Focus may easily be part of “inflating bubbles”.

Here I refer here to bubbles in finance, the price bubbles in real estate, political bubbles, opinion bubbles in social media and many other new bubbles on the rise, where millions of people within minutes pay attention to the same thing. A bubble can be defined as a phenomenon of “overheating” caused when huge crowds very suddenly do the same thing.

So-called bubble studies are investigating this lemming effect and its impact on our brain, social behavior and dynamics in society. They show that an important part of the formation of a bubble, for example through “likes” on social media, make hordes of people take certain steps – without much reflection. It is related to strategies that make it extremely easy to take very small steps, that are based on “doing something” instead of “stopping doing something”, focusing on very concrete and tangible results, that give people a sense of being recognized as part of something important.

For those who know SF and its way of working well, does that sound familiar?

Though it is certainly a provocative thought, the similarity between some of the aspects of inflating bubbles and the efficiency of SF are sufficiently clear to demand more attention when we work large-scale. I believe that being particularly careful with strengthening the SF reflection on steps, action and the noticeable impact, can reduce the risk of creating such lemming effects from effortless and spontaneous steps.

Certain large-scale contexts are particularly challenging, and it can be inevitable not to deal with corruption, violence of different kinds, or just the unethical codes of conduct frequently associated with power games in politics. This issue exists everywhere in different degrees, though Mexico is one of those countries that is struggling with a very critical situation on these issues. How to deal with these demanding scenarios deserves a whole article and is therefore outside this scope. Nevertheless, I will briefly mention the most common question I am asked: Is it at all possible to use SF in those kinds of settings?

As I have shared during this article, my experience shows that it is definitely possible! It is well known from applying SF that what is given attention will grow or will get strengthened. If we work in corrupt or ethically questionable environments, what should we pay attention to? According to the SF perspective it should be granted to what is needed and wanted, and not necessarily the obstacles. This is no different in extreme conditions, but even more important. Following this principle with discipline, SF can bring about important changes almost anywhere and anytime. However, what if what is wanted is not ethical? Then it is time to explore what they are trying to achieve…

As a modest example of this, a large group of police officers asked me to help them loosen up the procedures following international law forcing them to shoot a potentially dangerous person first in the leg, before killing him/her. They even spelled out in detail how everything would be easier if they could aim the first bullet towards the head. Sticking to SF principles, I did not morally question their need, but asked what difference it would make if they had it that way. Their answer was that without a living victim they would have a better chance in the legal process afterwards. Exploring how this would be noticed showed that what they wanted was a better legal defence for the police, not merely shooting people in the head. They felt abandoned by their institution when facing problems. That was definitely something we could work on….

This is the approach I call non-judging, though of course we will always make judgements. It is perhaps more precise to say that we explore in a very specific way instead of letting moral considerations lead the way.

While I find this “non-judging” approach to be at the core of SF, many do not share this view. There is a common notion of SF as an instrument for good intentions, and for creating a better world that apparently makes way for the opinion that “we” should not work with certain clients. If for instance, they are too powerful; if they do not represent humanistic views; if they are corrupt or have morally ill intentions.

These perspectives take us into a debate on the ethics of SF, which at this moment, only leaves us with further questions:

Is it part of our ethics that SF doesn’t judge? Is it contrary to ethics to favour the most powerful agents? And if this is coherent with what we want, how can we assure that we are “on the right side” and at the same time be non-judging? That is in itself a contradiction.

Are there any limits in our way of using SF and if so, how can they be defined.? Thinking big and acting large-scale with SF forces us to (re)think what we do, how we do it and what makes us do it. For those who are not interested in SF in large-scale settings, it might well be of importance to explore this topic anyway, just for the sake of observing and testing SF from a new perspective that shows aspects and details not visible from other stand points.

Or perhaps this perspective is not new at all. What if Peter Szabo3 is right that there is an important difference between thinking that change is happening all the time, or believing that change has already happened.?

Following this, we get back to the start of this article where I first posed the question whether we can use SF to think big or if SF is already in big thinking in general. As mentioned, this question is more than rhetorical. It does make a difference. If we assume that SF has strong similarities with big thinking in general, it means that SF is by nature part of large-scale issues. It is this combination of exploring questions from an open, flexible and unbound perspective, integrating diversity, searching for details on what works and what has not even happened yet that are implied in big thinking, and precisely what is needed when managing large-scale challenges.

I believe that SF is already in big thinking and is already in large-scale processes. We just have to pay sufficient attention to make it grow.

It implies that SF is much more than a technique, a method or a set of principles. And it frees us from limiting our exploration of SF ideas and formulations only to SF settings, as they could indeed be anywhere where big thinking and acting take place.

This drive for allowing SF to exist outside its own settings, made me discover SF large- scale questions in all kinds of environments and moments in history. Among them, I heard about a Chinese philosopher, who took the first step towards a great oriental empire with the following question: “What is needed to create good men that can be offered to our women?”

This is a question that has intrigued me for months: • The neutrality and openness inherent by asking “what is needed”. The question avoids pointing out responsibilities as it would have been, had it been addressed as “who needs to do what?”. At the same time, it avoids creating hierarchical distance as if he had asked “what do we have to do…?”. • It implies that something has to be done to facilitate being “a good man” • It states that women’s value in society is unquestionable and its worship is fundamental for development • And finally, all this shows an enormous humility embedded in the question. This in itself is a recognition of the people to whom it is directed.

I wonder, and I ask you and everyone who reads this, what is our appointment with thinking big with SF? Knowing what we know about the efficiency and contribution of SF in large-scale settings, what is our role? What questions can bring about constructive change in this new world order we are now witnessing – and how loud should we pronounce them?

In other words, which SF large-scale questions should be ours?

This article was originally the keynote speech at the Third Australian and New Zealand Solution- Focused Conference held in Adelaide, 2017 and has been updated.

Aoki, Yasuteru, 2016. “SF Inside, Why the “SF Inside” can be useful in organisational development”, in Solution Focused Practice in Asia, ed. by Debbie Hogan, David Hogan, Jane Tuomola, Alan K.L. Yeo. Routledge.

Comment during conference by Peter Szabo at the Danish Solution-Focus Conference in Copenhagen, 28th of April 2016.

pdf: Managing Complexity in Large Scale Processes – Thinking big with Solution Focus