How to change everything by changing as little as possible

By Dr Mark McKergow

Co-director, sfwork – The Centre for Solutions Focus at Work

It’s common knowledge in the business world that change is very difficult. Managing change is hard work, creating change takes lots of effort, top management support is vital and yet elusive, and great care has to be taken to make sure it all doesn’t go horribly wrong. At least so it is said…

Would it surprise you to know that a new approach to change is gathering momentum fast in the business and organisational world? Solutions Focus (SF) comes originally from the world of mental health and psychological change, where it is transforming our understanding of people and how they work. It’s also making inroads in business all over the world – global names including Nationwide Building Society (UK) , Royal Bank of Canada, Lufthansa (Germany) and Canon (Japan) are benefiting right now.

Problem Focus and Solutions Focus

Are there times when you want something to be different, and just don’t know what to do? Of course there are. So rather than embark on that expensive change programme, why not investigate this approach – it’s fast, effective, energising, engaging, flexible, low cost…and somewhat counter-intuitive.

Here’s a thought to begin with – one definition of SF:

Change is happening all the time… The simple way to change is to find useful change and amplify it

When something’s wrong, we have the idea that the way to change is to find what’s wrong and fix it. The usual strategy goes something like this:

- Diagnose the problem

- Discover the cause and address weaknesses

- Make detailed action plans

This works very well in many situations – fixing your car for example. You take it to the garage and you want them to look at it, find what’s wrong, fix it and give it back to you. This strategy works well for situations where things are fixed and well-known in advance, and where your efforts don’t themselves change the situation dramatically.

Introduce people into the equation, however, and things aren’t so easy. For decades psychologists have been trying to find ways to classify people and their problems so that the basic ‘problem-focused’ strategy will work. The results have been less than startling. However, the good news is that there is a better way – a way which not only works reliably but also saves a great deal of time and effort on everyone’s part. It’s relatively quick to learn, and also a positive experience to do. It’s called Solutions Focus.

SF takes a quite different approach to working out what to do. To start with, it doesn’t use ANY of the conventional problem-focused steps above. Wait a moment… how on earth can you make progress without knowing exactly what the problem is? Surely we have to address the underlying causes if we wantlasting success? The fifty years of experience, development, research and practice into the SF approach shows differently.

SF – The Direct Route

So, what are we going to do instead? Rather than the problem-focused route described above, we can look at SF as taking three contrasting steps:

- Describe what’s wanted instead

- Discover what’s working already and find strengths

- Take small steps

At first glance this looks so obvious it’s hardly worth talking about. And yet the process of discussing, deciding and acting on these things – and not doing the other things – can transform even the most difficult situation. Professionals who work in the most challenging situations – top executives, consultants, psychiatrists, teachers, change agents – are all discovering the simple power of SF.

The reasons for this become clearer when we have a look at the contrast between working with a problem focus and a solutions focus.

Problem Focus

- What’s wrong?

- What needs fixing?

- Blame

- Control

- Causes in the past

- The expert knows best

- Deficits & weaknesses

- Complications

Solutions Focus

- What’s wanted?

- What’s working?

- Progress

- Influence

- ‘Counters’ in the past

- Collaboration

- Resources & strengths

- Simplicity

- Actions

(from Jackson and McKergow, 2007)

An example – An Inspector Calls

The chemical site had a problem, and it was looming larger – with a threat of closure from a new safety inspector. The plant had seen plenty of change over the years, with old machinery decommissioned and new processes brought on stream. Safety, which had always been a key issue, was now managed by a plant safety team in conjunction with the safety regulator’s site inspector.

The inspector had a great deal of power – he could go wherever he wanted on site, enforce improvement notices (potentially at great expense), and ultimately could stop operations and close down the plant. In the past, working relations with successive inspectors had been reasonable. But now the new inspector was proving uncooperative when presented with the plant team’s latest plans to improve the site’s safety culture.

The team members had been expecting support from the regulator, and were surprised by his officious attitude: he wanted to see every piece of paper and was reluctant to engage in the customary informal exchanges with managers.

The team tried all their regular good tactics for getting along, but to no avail. As stories spread – “You can’t get a straight answer out of him…” “He’s not interested in anything except the paperwork…” “He’s out of his depth, you know…” “He won’t stop till he’s found something wrong.” – a sense of despondency gripped the site.

The safety team knew the essence of the problem: the inspector was stopping them from making progress with their safety culture plans and a worsening impasse would threaten the very future of the site, with appalling knock-on effects for their parent company.

Traditional problem-focused ways of approaching the situation might include:*

- An examination of why the inspector wouldn’t see sense

- A ‘barrier analysis’ of what was impeding matters

- A psychological profile of the inspector, to establish the cause of his behaviour

- Attacking the inspector by official complaints to his seniors

- A workshop with the inspector to firm up the nature of his concerns

- Writing off the time and money invested in the safety culture project and starting again

The safety team brought us in to help, perhaps suspecting that we would begin by setting up a mediation between them and the inspector.

Instead, we took a solutions focus, asking them to rate their encounters with him on a scale of 0 – 10. One manager quickly snorted – “Zero!”. We paused and waited. “…apart from once, when it was a three for 20 seconds…”

Suddenly there was a glimmer of hope. The crux of the solution, we figured, would be in those few seconds. Not in any of the traditional approaches, and not even requiring conscious action from the inspector. The solution was not going to centre on him as an individual, with all his “flaws, failings and difficulties”, but on the interactions between him and the safety team. We needed to know more.

When we asked the manager what he had done to bring about this dramatic, if brief, improvement, he said “I suppose I stopped pushing him for a moment and gave him time to think.”

The mood of the meeting palpably changed. The team outlined the parts they had individually played in their own best exchanges with the inspector, and from these strands drew out a list of 14 actions that they could do quickly, simply and cheaply to move just one point up the scale.

These included bringing fewer people to meet the inspector, wearing name badges at meetings and giving him more notice of impending questions and issues. The individual who had most contact with the inspector was tasked with noticing what was working best.

Instead of gloom at their lack of options, the managers said they now felt refreshed to be analysing what was going well instead of what was going badly.

When we followed up some weeks later, matters were much improved. The threat of an improvement notice had been lifted, and the project was back on track. One manager said that she know they were making real progress when the ‘impersonal’ inspector had enquired about her recent holiday!

(from Jackson and McKergow, 2007)

You will notice that our role in this case was mostly in asking great questions, gently keeping the people on the SF track and away from the problem track, and helping them build on and expand their awareness and knowledge of the situation. The SF approach has parallels in the work of philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, who wrote:

“We learn by rearranging what we know” – Ludwig Wittgenstein

This might be one way to think about working in an SF way. By helping those around you rearrange what they – and you – know about the situation, then whatever needs to happen next becomes clearer. You have stripped away the confusion and muddle, and arrived at a more useful understanding. And imagine being able to do that quickly and effectively – in a meeting, running a project, dealing with a difficult person, in a negotiation, building business strategy…

So let’s look more closely at how to do it.

Understanding SF – The Albert Model

I named this model after Albert Einstein, who once commented very sagely that

“Things should be made as simple as possible – but no simpler” Albert Einstein

It’s the last three words that make this difficult, of course. Anyone can simplify something by leaving stuff out. You could simplify a motor car considerably by leaving out the engine. However, that would be too simple – it wouldn’t work! The challenge is to simplify whilst leaving the process effective. This diagram gives us some clues about what to leave in and what to overlook and leave out.

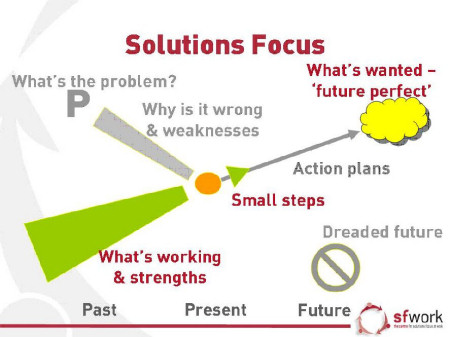

In the diagram, time runs from left to right. The present is in the middle, with past and future either side. You will notice a problem axis – running top left to bottom right. There’s a problem we want to work on, and it started some time ago – so the problem and its causes lie in the past (top left). Here also are the weaknesses which may be contributing to the problem. There is a matching ‘dreaded future’ bottom right – the place we’ll end up if the problem goes unchecked and unresolved. That’s the problem axis.

The solution axis is quite different. The ‘future perfect’ – our term for what is wanted – is top right. Aligned with it bottom left is the solution-focused past – evidence of what’s wanted happening already in various ways, and of related strengths and resources. This is the part of the diagram that is usually overlooked and ignored – and yet it contains the most useful and relevant information! Often, of course, people in difficult situations assume that they will draw a blank by looking here. One of the skills of using the SF approach is to gently and relentlessly probe to uncover the useful nuggets in this area.

People usually assume that the problem axis has to be investigated and understood before progress can be made. However, in complex situations we find the opposite is the case: studying the problem and its causes is unhelpful in all kinds of ways. It makes you an expert in the problem – when what you want to be is an expert in how to do something else! And it tends to promote discussions of blame and demotivation, just at the moment when you want collaboration and engagement. And it takes up time you could be using more usefully.

Let’s look at the four main contrasts of the Albert Model in more detail.

What is wanted vs What’s wrong

What’s working vs Why things are wrong

Strengths vs Weaknesses

Small steps vs Action plans

What is wanted vs What’s wrong

When you go to the supermarket, you go with a list of what you want. It helps keep your shopping trip on track, and you come back with the right things. Situation normal. You wouldn’t go shopping with a list of the things you didn’t want… would you? Think about it; it would be a very long list indeed. And trying to work out, from looking at this list of thousands of items, what you did want would be a nightmare. And yet… this is precisely the problem-focused approach!

In the SF approach we have an unique and interesting way to compile our ‘shopping list’ – we call it Future Perfect.

Suppose… that you wake up tomorrow and suddenly and miraculously, everything is working the way you want…what would be the first tiny signs that would tell you? Who else would notice? What would they notice? What else? And so on.

Notice that this is not really goal setting in the usual sense. Here, we are imagining a day when it’s happened – the tiny details, the impact on everyone around us, the signs by which we discover it. These are usually small and everyday – even if the change has been dramatic and life-changing. Taking time working out what you want is rarely time wasted.. as long as you take it forwards to the next stage.

What’s working vs Why things are wrong

Having described our Future Perfect – the signs of the things we want to happen – we can now move on to make connections with what’s already working. You might think that the answer to what’s working would be ‘Nothing, dummy… that’s why it’s a problem!’. This is very rarely the case.

One practical SF tool to do this is the Scaling tool. It’s deceptively simple.

Imagine a scale from 1-10, where 10 is the Future Perfect and 1 is the exact opposite. Where are you right now on that scale?

The answer to this is rarely zero – it might be, say, a three. So how come it’s three already? What’s already working? What else? What else? We can build up a list of elements that are already happening – perhaps a little, perhaps some of the time. Occasionally we find startling examples where nearly the whole Future Perfect happens already – but the connection has never before been made. Here’s one such example.

Safety in the Shade

Safety is vital in chemical plants. Personal safety is particularly important, and it is a legal requirement for firms to provide personal protective equipment, such as overalls, helmets, gloves and safety glasses, to their workers. Getting people to wear this equipment is, however, another matter. Often the workers have spent many years operating the plants and have stopped noticing the risks around them.

One such chemical plant was jointly operated by Zeneca in Italy. The managers (and the law) wanted people to wear safety glasses. The workers, though, were reluctant. The solution emerged when someone asked themselves ‘When does this Future Perfect even partially occur? When do our people wear glasses anyway – even when they don’t strictly need to?’. We’re talking Italian men here. When do Italian men wear glasses when they don’t need to – when they are cool, fashionable sunglasses!

So they commissioned a set of safety glasses made with mirror shades, and made them available in the same way to operators on the factory floor. And a miracle did happen – the workers instantly began wearing them most the time. Even outside the chemically hazardous areas, in fact. From just a small change in the design came this very significant change in behaviour.

Now, the firm could have chosen a problem focus instead – they could have studied the reasons for people not wearing the old safety glasses, their motivations for risking themselves and their health, the underlying causes of accidents around the world. Would this solution have emerged from such an inquiry? We guess not.

(from Jackson and McKergow, 2007)

Strengths vs Weaknesses

Many organisations I know have personal development plans for their employees. These plans usually feature two lists of personal qualities: strengths (which are good) and ‘areas for development’ (which need developing). Of course, everyone knows that ‘areas for development’ is a polite way of saying ‘weaknesses’. There seems to be the idea that if only we could develop our weaknesses, everyone would be a fine, balanced and excellent human being.

Only it’s not like that at all. What makes people great contributors to the success of an organisation? Why, it’s their strengths! So, how would it be if we asked people to develop and build further on… their strengths. World class performers are world class precisely because they excel at their strengths. Tiger Woods is surely the finest golfer in the world. I also hear that he is not a particularly good cook. But guess what – it doesn’t matter! This applies to golf as well – Butch Harmon, who coached Tiger for many years, once suggested to Tiger that he practise his bunker shots. “No, Butch”, replied Tiger. “I need to practise my approach shots – that way I won’t get into the bunker in the first place.”

People often ask me if this means we never need to address weaknesses. Of course not. If someone is messing up at their job, and they need to keep doing it, then something has to be done. However, this is damage limitation rather than development. You might also ask how the individual managed to get the job in the first place and address recruitment procedures. But real development means building on strengths.

Small steps vs Action plans

Conventional management approaches always seem to involve action plans to meet targets. Today our health service and schools are driven by dozens of government imposed targets. And yet improvement is patchy, and sometimes whole areas are overlooked because they weren’t in the action plan.

When former Prime Minister Harold MacMillan was asked about the greatest challenge he faced as a statesman, he famously replied ‘Events, dear boy, events’. Things come along that you hadn’t planned for, which throw everything off track. Everywhere I go people have the same experience – and yet we keep on making our action plans. The SF approach provides a useful alternative – small steps.

Rather than trying to lay out a plan for action, we arrive a first small steps – steps that can be taken tomorrow, cost little, and move things forwards. These steps are taken, and shortly afterwards we can assess progress – ‘what’s better?’. If things are better, then we can continue secure in the knowledge that we are moving in the right direction. If not, we can reassess. When events appear, we can respond to them – without having wasted a great deal of energy on longer term plans that will not now be of any use.

One way to do this in practice is to return to the scale you set up earlier. Remember, the scale from 1-10, where 10 is the Future Perfect, and you now know lots of things that are getting you to a three. Having listed all these things, go ahead and ask yourself

What would a four (one point higher) look like? What signs would tell me I’m at a four? What are some small first steps in this direction?

There are good reasons for the lack of success of the plan-and-do approach in complex environments. The latest findings from ‘complexity science’ shows how impossible and intractable such situations can be. In any case, the small steps approach has the benefit of fast and effective targeted action, which gets things moving and boosts motivation too. Try it.

Business applications

The SF approach sounds like a simple idea…but turns out to be counterintuitive in many ways. However, it’s applicable to all kinds of business situations. My latest book with Jenny Clarke – Solutions Focus Working: 80 real-life lessons for successful organisational change – describes real cases from organisations around the world in the areas of

- Strategy

- Quality improvement

- Morale

- Sales

- Project management

- Everyday management

- Reorganisation

- Stakeholder management

- Training

- Outplacement

- Leadership and change

- Business disasters

For one manager’s view of how SF has helped her in her role, I spoke to Antoinette Oglethorpe, European Learning & Organizational Development Director with XL Capital Ltd.

In the current climate, many HR professionals are being asked to become strategic’business partners‘; all the usual administrative stuff is being outsourced or at least assigned to a shared service centre, and specialist areas like recruitment, compensation and benefits etc are going into centres of expertise leaving the HR Generalists to “partner” with the business in helping them achieve their business goals through people. However, many of us are not sure exactly how to carry out this new role.

To play the role of business partner, it’s often said that ‘you need to understand the business’. Thankfully, SF offers a way to really support the businesswithout the need to fully understand every aspect. It enables you to ask intelligent and relevant questions confidently without already needing to know everything about the setting. In many ways, you end up coaching the line managers to find a way forward.

SF would be a very productive way to manage processes like salary reviews. HR professionals often struggle to say ‘No!’ for fear of being perceived as not business-focussed and have to resort to hiding behind policies. SF helps them get involved more easily and start saying Yes more – and more carefully. The idea of not-knowing helps a lot – and while it’s a coaching model, this is definitely not the old ‘manager-as-coach’ idea. It’s a great way to quickly build collaboration and work together.

In my people development role I use scaling a lot – for example in team development, with the manager and then with the whole team. I ask them things like, ‘Imagine a scale from 1-10, where 10 is the best the team has ever been…where are you now?’. I think they like the fact that it all sounds rather scientific and precise, even though the whole approach is really just a way into a useful conversation. It helps you to find what’s working, and find some next steps to move from say a 6 to a 7. If you just ask them ‘how would you like the team to be’, you end up with a huge wish-list. This way, it’s done in 15 minutes and everyone’s happy to be making progress.

The fact that this approach is brief is a big advantage in many situations. One of the challenges of my job is working with people across many international locations. I use SF in performance management with my subordinates – both face to face and over the phone. Also, I use it to work with our high-potentialemployees – they have constant time pressures, so staying brief is very valuable and practical. It certainly doesn’t take a whole hour’s conversation to achieve some useful progress.

I have also found SF an excellent way to raise my profile within the company. Being seen to be asking intelligent questions is a good – and relatively safe – way to be noticed. Also, HR has an ongoing challenge of building a positive reputation with the business, so this is all to the good!

I like to use SF as a way to turn people around. Employees don’t usually come to me to tell me happy they are and how good everything is…they come because something is wrong or needs fixing. This way I can be listening to them and moving on very quickly – without them feeling rushed or unheard. Employees often come to HR when they are fed up and thinking of leaving, and I have been able to help them feel better about the company and thereby increase retentionthis way too.

All in all, HR can be a very reactive job. SF gives you a way to approach things quickly and effectively. When waves of negative emotion come your way, you can handle it smoothly and turn it around. When people are focusing on what’s working, you can quickly help them find ways to make progress. Then you can all get on with what’s next.

Conclusion

To summarise, SF can help you move forwards, build change, stay positive and save time and effort. It’s tried and tested and in use all over the world.

To find out more, visit our website at www.sfwork.com. There you’ll find information about books, training, user groups and lots more. Join the companies that are using SF by getting in touch with us today.

References

Paul Z Jackson and Mark McKergow The Solutions Focus: Making coaching and change SIMPLE, Nicholas Brealey Publishing, second edition (2007)

Mark McKergow and Jenny Clarke Solutions Focus Working: 80 real-life lessons for successful organizational change, SolutionsBooks (2007)